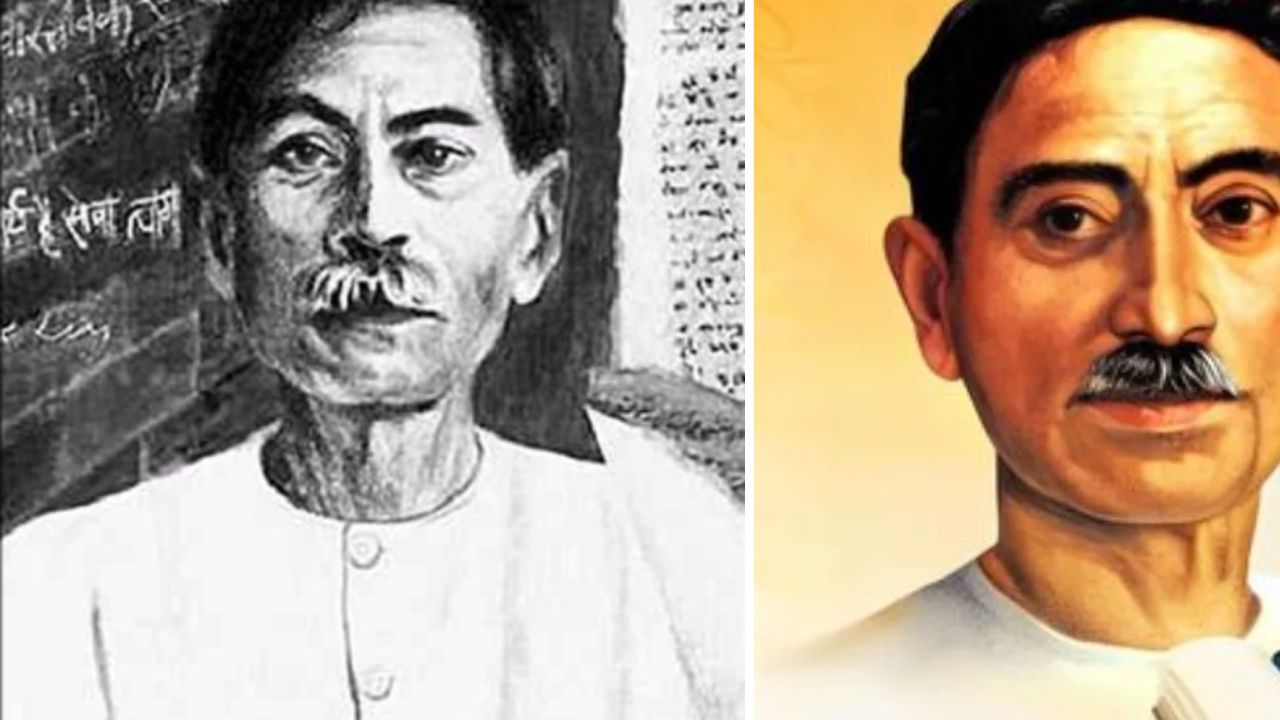

Friends, our country has for centuries been the birthplace and land of countless great personalities brimming with virtues – sages, poets, writers, musicians, and many more. Thousands of works created by these luminaries are invaluable. Today's youth, in this digital age, seem to be losing their way, drifting further and further from our heritage and precious treasures. subkuz.com consistently strives to bring you these invaluable treasures, along with entertaining stories, news, and information from India and around the world. Presented here is one such invaluable and inspiring story by Munshi Premchand.

The Bank's Bankruptcy

In the Lucknow National Bank office, Lala Saindas reclined on a comfortable chair, studying share prices and pondering how to distribute profits to the shareholders this time. He considered buying shares in tea, coal, or jute; speculating in silver, gold, or cotton; but the fear of losses prevented him from making any decisions. This year's speculative trading had resulted in significant losses; a fictitious profit-and-loss statement had to be presented to encourage the shareholders, and the profit had to be paid from the bank's capital. This made him hesitant to engage in speculative trading again.

However, leaving the money idle was impossible. Within a day or two, he needed to find a suitable investment; the quarterly meeting of the directors was scheduled within a week, and if no decision was made by then, nothing could be done for the next three months, necessitating another fraudulent exercise at the time of the half-yearly profit distribution – something increasingly difficult for the bank to sustain. After much deliberation, Saindas rang the bell. A Bengali clerk poked his head out from the adjacent room.

Saindas – Write a letter to the Taj Steel Company requesting their new balance sheet.

Clerk – They don't care about money. They don't respond to letters.

Saindas – Alright, then write to the Nagpur Swadeshi Mill.

Clerk – Their business isn't doing well. Their workers recently went on strike; the mill remained closed for two months.

Saindas – Oh, so write to someone! In your opinion, the whole world is full of dishonest people.

Clerk – Sir, we can write to everyone, but writing alone doesn't yield any profit.

Lala Saindas had become the Managing Director of the bank due to his family reputation and prestige, but he was unfamiliar with practical matters. This Bengali clerk served as his advisor, and the clerk had little faith in any factory or company. Due to this mistrust, the bank's money had remained untouched in the previous year, and the same situation seemed to be repeating itself. Saindas couldn't find a solution to this problem, lacking the courage to venture into any business on his own. Restlessly pacing his room, he was informed by the doorman that the Maharani of Barhal had arrived.

Lala Saindas was startled. The Maharani of Barhal had been in Lucknow for three or four days, and everyone was discussing her. Some were captivated by her attire, others by her beauty, and still others by her free-spirited nature. Even her maids and guards were subjects of public conversation. Crowds gathered at the gates of the Royal Hotel. Many curious people, perfumers, brokers, and even tobacco sellers, had come to catch a glimpse of her. Wherever the Maharani's procession passed, the onlookers would exclaim, "Wow! What magnificence! Such a splendid entourage is rarely seen, even among kings and nobles! And the decorations are exquisite! Such fair-skinned people are not even seen here. The local nobles, I don't know what they eat – Mrigaank, Chandrodya, and God knows what else – but there's no glow or radiance on their faces. I wonder what food and water they consume that makes them look like fresh apples! It must be the climate."

Barhal was a princely state in British India, near Nepal in the north. Although the public considered it very wealthy, its actual revenue did not exceed two lakh rupees. However, its area was vast, much of the land being barren and uncultivated. The inhabited part was also mountainous and arid. Land was very cheap.

Lala Saindas quickly changed into a silk suit and sat majestically at his desk, as if the arrival of royalty was commonplace. The office clerks straightened up; a hush fell over the bank. The doorman adjusted his turban; the watchman drew his sword and stood at his post. Even the sleepy punkah-wallah woke up, and the Bengali clerk went outside to greet the Maharani.

Saindas maintained outward composure, but his mind was a flurry of hope and fear. This was his first interaction with a queen; he was nervous about whether he would manage to converse appropriately. The behavior of royals was unpredictable. He worried about making a mistake. He felt a lack of preparation; he was unfamiliar with royal etiquette. How should he show respect? What should he be mindful of during conversation? How much humility was appropriate to maintain decorum? These questions perplexed him, and he wished to get the ordeal over with quickly. He usually dealt with traders, minor landlords, or nobles with formality and directness, and with educated gentlemen with politeness and courtesy. On those occasions, he didn't need much thought; but this time he was deeply troubled, like a Lankan in Tibet, unfamiliar with the customs and language.

Suddenly, his gaze fell upon the clock. It was four in the afternoon, but the clock was still asleep. The date hand had outpaced even time itself. He quickly got up to set the clock, just as the Maharani entered the room. Saindas left the clock and stood beside the Maharani, unsure whether to shake hands or bow. The Rani herself extended her hand, relieving him of his dilemma.

Once seated, the Rani's private secretary initiated conversation. After recounting the history of Barhal, he described the improvements made under the Rani's efforts. Ten lakh rupees were needed to construct a new canal branch; but they preferred to deal with an Indian bank. It was now up to the National Bank to decide whether to seize this opportunity.

Bengali Clerk – We can provide the loan, but we need to see the paperwork.

Secretary – Do you require collateral?

Saindas generously replied – Sir, your word is sufficient collateral.

Bengali Clerk – Do you have any financial statements from the princely state?

Lala Saindas disliked his head clerk's worldly approach. He was intoxicated by generosity. The Maharani's presence was ample security. Discussing documents and accounts seemed like petty business to him, reeking of distrust.

In the presence of women, men often become shy and reserved. Saindas looked sternly at the Bengali clerk and said – Checking the documents is unnecessary; we should simply trust.

Bengali Clerk – The directors will never agree.

Saindas – We don't care; we can give the loan on our own responsibility.

The Rani looked at Saindas with gratitude; a slight smile played on her lips.

However, the directors deemed it necessary to examine the income and expenditure accounts, a task entrusted to Lala Saindas, as no one else had the time to scrutinize the entire office's records. Saindas complied, spending three or four hours reviewing the accounts before writing a report to his satisfaction. The matter was settled; the documents were signed, and the loan disbursed. The interest rate was set at nine percent.

For three years, the bank's business thrived. Every six months, a bag containing forty-five thousand rupees would arrive without prior notice. Traders were given five percent interest, while shareholders received seven percent profit.

Everyone was pleased with Saindas; his shrewdness was praised. Even the Bengali clerk gradually became a believer. Saindas would tell him – "Clerk, trust has not disappeared from the world, nor will it ever. Trusting in truth is the duty of every human being. A person devoid of trust is as good as dead; he feels surrounded by enemies, even the greatest saints seem deceitful. Even the most patriotic individuals appear to him as hungry for praise. The world seems full of deception and treachery to him; even his faith in God diminishes."

A famous philosopher said, "Consider every person to be good-natured until you find direct evidence against them." The current system of governance is based on this important principle. And one shouldn't harbor hatred towards anyone. Our souls are pure; hating them is like hating God. I'm not saying there's no deceit in the world – there is, and in abundance – but it is not remedied by mistrust, but by understanding human nature, a God-given quality. I don't claim infallibility, but I believe I can understand a person's inner feelings just by looking at them. No matter how much they disguise themselves, their true nature cannot deceive my insight.

It should also be noted that trust breeds trust, and mistrust breeds mistrust – this is a natural law. A person whom you initially perceive as cunning, deceitful, and wicked will never deal with you honestly. He will try to undermine you. Conversely, even if you trust a thief, he will become your servant. He may rob the entire world, but he will not betray you. No matter how wicked or unrighteous he may be, you can lead him wherever you want by putting the chain of trust around his neck; he can even become a virtuous soul in your hands.

The Bengali clerk had no answer to these philosophical arguments.

It was the first of the fourth year. Lala Saindas sat in the bank office, waiting for the postman. Forty-five thousand rupees were expected from Barhal today. This time, he intended to buy some decorative items. The bank still lacked a telephone; he had already ordered one. Hope shone on his face. He would laughingly tell the Bengali clerk – "On this date, my palms start itching. My hand is itching today too. He would say to the office staff – "Oh Munshi Sharafat, let's see the auspicious sign; is it just interest, or is there a bonus for the office staff as well?" Hope has its own effect. The bank seemed unusually bright today.

The postman arrived on time. Saindas looked at him casually. He took out several registered envelopes from his bag. Saindas glanced at the envelopes. There was no envelope from Barhal – no seal, no familiar handwriting. A sense of disappointment washed over him. He almost asked the postman if any registered mail was missing, but he stopped himself; such impatience would be inappropriate in front of the office clerks. But when the postman was about to leave, he couldn't help himself and asked – "Hey brother, didn't any registered envelope get left behind? It should have arrived today." The postman said – "Sir, such a thing is impossible! Even if there is a mistake somewhere, how could there be a mistake in your case?"

Saindas's face fell, like water spilled on fresh paint. After the postman left, he said to the Bengali clerk – "Why is this delay? This has never happened before."

The Bengali clerk replied impassively – "It might have been delayed for some reason. There's no need to worry."

Despair makes the impossible possible. Saindas now thought that perhaps the money had arrived as a parcel. It was possible that a parcel containing three thousand ashrafis had been sent. Although he didn't dare to reveal this thought to others, he clung to this hope until the parcel delivery man returned. Finally, in the evening, he left in a state of anxiety. Now he awaited a letter or telegram. He got up irritably two or three times, thinking of writing a letter and stating clearly that failing to keep a promise in a business deal is a betrayal. Even a day's delay could be fatal for the bank. This would prevent any future complaints; but after further thought, he decided against writing.

Evening arrived, and several friends came. They started chatting. Then, the postman delivered the evening mail. Usually, he would open the newspapers first, but today he opened the letters, but there was no letter from Barhal. Then, breathlessly, he opened an English newspaper. The headline of the first telegram sent a chill down his spine. It read:

“The Maharani of Barhal passed away last evening after a three-day illness.”

A short note further stated – "The untimely death of the Maharani of Barhal is a tragic event not only for her principality but for the entire province. Eminent physicians had not even been able to diagnose her illness before death claimed her. The Rani always kept the progress of her principality in mind. The benefits that her principality received during her short reign will be remembered forever. Although it was understood that the state would pass to another after her, this thought never hindered the Rani's performance of her duties. According to scriptures, she did not have the right to take loans on the security of the principality, but for the welfare of her subjects, she had to violate this rule many times. We believe that if she had lived a few more days, she would have freed the principality from debt. She constantly worried about this. But this untimely death has now left this decision to others. We must see what happens to these debts. We have reliably learned that the new Maharaja, currently residing in Lucknow, has, in accordance with the advice of his lawyers, refused to repay the debts of the deceased Maharani. We fear that this decision will cause a great stir in the money-lending community and will teach many wealthy people of Lucknow how harmful greed for interest is."

Lala Saindas placed the newspaper on the table and looked towards the sky, the ultimate refuge of despair. Other friends also read the news. A debate ensued, with all the blame placed on Saindas; his past efficiency and foresight were forgotten. The bank was unable to bear such a massive loss. Now the question arose of how to save his own life.

As soon as the news spread through the city, people became anxious to withdraw their money. A line of creditors formed throughout the day and night. Those who had deposits in current accounts withdrew immediately without explanation. This was the result of the article; the National Bank's reputation was ruined. If they had acted calmly, the bank might have recovered. But which ship can remain stable in a storm? Finally, the treasurer declared bankruptcy; so much blood was drained from the bank's veins that it died.

Three days had passed. Thousands of people gathered in front of the bank's house. Armed soldiers guarded the bank's doors. Various rumors were circulating. Sometimes news spread that Lala Saindas had committed suicide; sometimes, it was reported that he had been arrested; sometimes, that the directors had been imprisoned.

Suddenly, a motorcar emerged from the street and stopped in front of the bank. Someone said – "It's the Maharaja of Barhal's motorcar." Hearing this, hundreds of people rushed towards the car, surrounding it.

Kunwar Jagdish Singh had come to Lucknow to consult lawyers after the Maharani's death. He also had many purchases to make. Desires long held in abeyance now surged forth like pent-up water. He had acquired the motorcar only that day and was negotiating for a mansion in the city; a wagon laden with valuable luxuries was already on its way back to Barhal. Seeing the crowd, he thought some new drama was about to unfold and stopped the car. In a moment, hundreds had gathered.

Kunwar Sahib asked – "Why have you all gathered here? Is there some spectacle about to happen?"

A gentleman, who appeared to be a somewhat disheveled noble, said – "Yes, a very entertaining spectacle."

Kunwar – Whose spectacle is it?

He said – "Fate's."

Kunwar Sahib was surprised by this answer, but he had heard that Lucknow residents were known for their witty remarks; thus, he felt he should respond in kind. He said – "There's no need to come here to watch fate's game."

The Lucknow gentleman said – "You're right, but where else would one find such entertainment? Here, between morning and evening, fate has transformed many from rich to poor, and from poor to beggars. Those who sat in palaces just a week ago now struggle for a morsel of bread. Those who considered the vicissitudes of fortune and time as mere poetic metaphors now lament in a way that would shame even the most heartbroken lovers. Where else will you see such a spectacle?"

Kunwar – Sir, you've made the riddle even more obscure. I am a simple country person; please speak plainly.

To this, the gentleman said – "Sahib, this is the National Bank. It has gone bankrupt. Do you recognize me?"

Kunwar Sahib looked at him, jumped out of the car, and shook his hand, exclaiming – "Oh, Mr. Naseem? You here? I'm so glad to see you."

Mr. Naseem had studied with Kunwar Sahib at Dehradun College. They had often strolled together in the Dehradun hills, but since Kunwar Sahib had left college due to family troubles, the two friends had not met. Naseem had also returned to his home in Lucknow shortly after.

Naseem replied – "Thank God you recognized me. Well, it's a terrible situation. Whatever capital I had is now gone. This bankruptcy has reduced me to a pauper. Now I shall come to your doorstep and protest."

Kunwar – You have a home; come without hesitation. Why don't you come with me? I must say, I had no idea that my refusal would have this consequence. It seems the bank has ruined many.

Naseem – There is mourning in every house. I have nothing left but these clothes.

At that moment, a "tika-wearing Pandit" arrived and said – "Sahib, you at least have clothes. There is no place for anyone here, neither on earth nor in heaven. I'm a teacher at the Raghoji School; all the school's funds were deposited in this bank. Fifty students rely on it for their education and food. The school will close tomorrow. The students are from far away; God knows how they'll reach their homes."

A gentleman with a Punjabi turban, a dark coat, and chappals stepped forward and, with an air of leadership, said – "Sir, this bank's failure has destroyed many institutions. Lala Dinanath's orphanage can no longer function; one lakh rupees are lost. Fifteen days ago, I returned from a deputation and deposited fifteen thousand rupees in the orphanage fund, but now there is nothing."

An old man said – "Sahib, my life's savings are gone. Now I don't even have the assurance of a shroud."

Gradually, more people gathered, and general conversation began. Each person shared their woes with their neighbor. Kunwar Sahib stood with Naseem for half an hour listening to these tales of misfortune. As he was about to get into his motorcar and depart for the hotel, his eyes fell on a man sitting with his head bowed to the ground. This was a shepherd boy who had played with Kunwar Sahib in his childhood. There had been no distinction of high and low back then; they had played kabaddi, climbed trees together, and stolen birds' nests. When Kunwar Sahib went to Dehradun for his studies, this shepherd boy, Shivdass, had gone to Lucknow with his father and opened a milk shop. Kunwar Sahib recognized him and called out loudly – "Oh Shivdass, look here."

Shivdass heard the voice but didn't raise his head. He kept looking at Kunwar Sahib, remembering those childhood days when he played gulli-danda with Jagdish, when they teased old Ghafoor Mian and hid in the house, when he would discreetly call Jagdish from the teacher's side, and when they both went to watch Ramlila. He believed that Kunwar Sahib must have forgotten him; those childish things were long gone. But when Kunwar Sahib called him by name, he happily lowered his head further and tried to slink away. Kunwar Sahib’s compassion knew no boundaries. But seeing Shivdass withdraw, Kunwar Sahib got out of the car, took his hand, and said – "Oh Shivdass, have you forgotten me?"

Shivdass could no longer control his emotions. His eyes welled up. He embraced Kunwar and said – "Forgotten? No, but I feel shy to come before you."

Kunwar – Do you run a milk shop here? I didn't know. Come, sit in this motorcar. Let's go to the hotel. I want to talk to you. I'll take you to Barhal, and we'll play gulli-danda again.

Shivdass – Please don't, or people will laugh. I'll come to the hotel. You're staying at that Hazratganj hotel, aren't you?

Kunwar – Yes, you'll definitely come, won't you?

Shivdass – If you call, how can I not come?

Kunwar – How are you sitting here? Is your shop running?

Shivdass – It was running until this morning. I don't know about the future.

Kunwar – Were your funds also deposited in the bank?

Shivdass – I'll tell you when I come.

Kunwar Sahib got into the motorcar and told the driver – "Drive towards the hotel."

Driver – You had ordered me to go to the Whiteway Company's shop.

Kunwar – I won't go there now.

Driver – Won't you go to Mr. Jacob, the barrister's either?

Kunwar – (Irritably) No, don't go anywhere. Take me straight to the hotel.

These scenes of despair and misfortune raised a question in Jagdish Singh's mind – what is my duty now?

Seven years ago, when the Maharaja of Barhal died in his youth after falling from a horse, and the question of inheritance arose, due to the Maharaja having no children, his closest cousin, Thakur Ramsingh, was entitled to the inheritance. He claimed it, but the courts declared the Rani as the rightful heir. Thakur Sahib appealed, even going to the Privy Council, but without success. He spent lakhs of rupees in litigation, losing his own property in the process, yet he refused to rest. He constantly harassed the widowed Rani, sometimes inciting the tenants, sometimes spreading rumors against her, sometimes plotting to entrap her in false cases; but the Rani was a woman of great resilience. She would bly counter every attack from Thakur Sahib. Of course, this struggle cost her considerable sums; since she couldn't collect money from the tenants, she had to repeatedly take loans. However, legally, she was not entitled to take loans. Therefore, she had to either conceal this fact or accept high interest rates.

Kunwar Jagdish Singh's childhood was spent in luxury, but when Thakur Ramsingh became exhausted from the litigation and began to suspect that the Rani's actions might endanger Kunwar Sahib's life, he sent Kunwar Sahib to Dehradun. Kunwar Sahib lived happily there for two years, but as soon as he reached the top of his class in college, his father passed away. Kunwar Sahib had to abandon his studies, return to Barhal, and bear the responsibility of supporting his family and dealing with his long-standing feud with the Rani. From that time until the Maharani's death, his life had been full of hardship. He had nothing but debts and the Rani's jewels to rely on. He also had the concern of maintaining family honor. Those three years were a difficult trial. He constantly dealt with money-lenders, his heart pierced by their relentless demands. He had to endure the harsh treatment and oppression of officials, but most heartbreaking was the behavior of his own relatives, who backstabbed him, using friendship and unity as a cover for their treachery. These hardships made Kunwar Sahib a sworn enemy of authority, despotism, and wealth. He was a very emotional man. His relatives' unkindness and the dishonesty of his countrymen left a dark mark on his heart. His love for literature made him an inquirer into human nature. Where this knowledge distanced him from civilization, it strengthened his beliefs in popular sovereignty and communism. He realized that if genuine goodwill existed, it was only found among the poor and the humble. In those difficult times, when darkness surrounded him, he sometimes caught a glimpse of true compassion in those humble quarters. He did not consider wealth a blessing, but rather a divine curse, capable of eradicating compassion and love from the human heart; a dark cloud overshadowing the bright stars of the mind.

But as soon as wealth turned against him after the Maharani's death, his philosophical defenses crumbled. His self-awareness vanished. Those who were like enemies became his friends, and his true well-wishers were forgotten. His communist ideals began to change drastically. Intolerance arose in his heart. Self-sacrifice gave way to indulgence; the bonds of decorum tightened around his neck. Those officials whose presence had caused him to change his demeanor became his advisors. He now closed his eyes when he saw the poverty and destitution that he once truly empathized with.

There is no doubt that Kunwar Sahib was still a communist, but he no longer possessed the same freedom in expressing his beliefs. His thoughts were now afraid of action. He had the opportunity to translate his words into deeds; but now his field of action seemed fraught with difficulties. He was an enemy of forced labor, but now ending it seemed difficult. He was a devotee of hygiene and public health, but now he feared opposition even from villagers if he spent money on it. He considered harshness in collecting revenue from tenants a sin, but now it seemed impossible to work without being firm. In short, many of the principles he had once believed in now seemed irrelevant.

But the distressing scenes at the bank awakened his compassion. He felt like a man sailing in a boat, enjoying the beautiful scenery of the coast, only to find himself in front of a cremation ground, witnessing burning corpses and the wailing of the bereaved, and stepping ashore to share their grief.

It was ten o'clock at night. Kunwar Sahib lay on his bed. The scene at the bank was playing out before his eyes. The same cries of lamentation echoed in his ears. A question arose in his mind – Am I the cause of this irony? I only did what I was legally entitled to. It's the fault of the bank's managers, who gave such a large loan without security; the creditors should hold them accountable. I'm not God or a magistrate to suffer the consequences of others' foolishness. Then, his thoughts changed – I have no reason to stay in this hotel. Forty rupees will have to be paid daily; four hundred rupees will be wasted. So much stuff was purchased unnecessarily. What was the need? My dignity can't be enhanced by velvet-cushioned chairs or glass decorations. If I rented a simple house for five rupees, wouldn't that suffice? I and everyone else could live comfortably; people wouldn't condemn me. Why worry about this? Those for whom I display this pomp and circumstance are starving. I could use ten to twelve thousand rupees to build a well and benefit thousands of poor people. I will not fall for people's tricks again. This motorcar is useless. My time is not so expensive that I should increase my expenses by two hundred rupees to save an hour or half an hour. Running around in front of fasting tenants is like beating them with a stick. Granted, they will be impressed, and hundreds of women and children will gather to watch me, but increasing expenses just for show is foolish. If other nobles do this, let them; why should I imitate them? Until now, two thousand rupees per year sufficed for my living; now four thousand is more than enough. Do I have any right to waste other people's earnings this way? I do no industry, no business, from which I gain profit. If my men have forcibly taken control of the area, what right do I have to share in their plunder? Those who work should receive the full fruit of their labor; the state only protects them from the oppression of others; it should get a fair compensation for this service. That's all; I am only appointed to collect this compensation on behalf of the state. Besides this, I have no other share in the earnings of these poor people. They are helpless, foolish, voiceless; we can torment them as much as we want right now. They are unaware of their rights. I don't understand my importance, but a time will come when they will have a voice, and they will know their rights. Then our situation will be bad. These luxuries keep me away from my people. My well-being lies in being among them, living like them, and helping them.

The state's revenue is one and a half to two lakh rupees annually, no more. Even if I had the courage, on what basis? Yes, if I became an ascetic, it's possible; if I don't die suddenly, this matter will be settled. Jumping into this fire is to destroy my whole life, my aspirations, and my hopes. Oh! What hardships I have endured in anticipation of these days. My father died worrying about this. This auspicious moment was a distant lamp for our dark night. We lived on it. We always talked about it, sleeping and waking. How much satisfaction and pride it gave us. Even during times of hunger, our demeanor remained dignified. After all this patience and satisfaction, how can I turn away from the good days? Then there is not only my worry, but many schemes for the progress of the principality which I have already thought about. Should I abandon these ideals along with my desires? This unfortunate Rani has badly trapped me. As long as she lived, she never let me rest. Now that she is dead, she has left this burden on my head. But why am I so afraid of poverty? There is no sin. If my sacrifice saves thousands of households from hardship and suffering, I should not turn away from it. Living only for pleasure is not our goal. Our honor, prestige, and glory do not arise merely from pleasure-seeking. Who knows the kings and queens who lived in palaces and indulged in luxury? It is their self-sacrifice and strict adherence to their vows that made them the suns of our community.

If Shri Ramchandra had spent his life in luxury, we would not know his name today. His self-sacrifice made him immortal. Our reputation does not depend on wealth and luxury. Whether I ride in a motorcar or on a pony, whether I stay in a hotel or a simple house, it's all the same. At most, the influential people will laugh at me. I don't care. I want to stay away from those people. If this condemnation benefits hundreds of families, I am not a man if I do not accept it happily. If by foregoing my horses and hunting, my servants and sycophants and self-serving friends, I can help thousands of rich and poor families, widows, and orphans, I should not delay. The fortunes of thousands of families are in my hands. My indulgence is poison to them, and my self-restraint is nectar. I can be nectar, why should I be poison? And it's wrong of me to call this self-sacrifice. It's a coincidence that I'm now the owner of this property. I didn't earn it; I didn't shed blood or sweat for it. Had I not inherited the estate, I would be struggling for my livelihood like thousands of poor brothers. Why shouldn’t I forget that I am the owner of this state? It is on such occasions that a person is tested. For years, I have studied books and been a follower of the principles of philanthropy. If I forget those principles now, if I allow self-interest to prevail over humanity and morality, then it will indeed be the height of my cowardice and selfishness. What was the point of becoming a disciple of Gita, Emerson, and Aristotle for the sake of self-interest? I could have learned that from my other brothers. What greater teacher than prevailing custom? Should I, like ordinary people, bow down to self-interest? Then what was my distinction? No, I won't violate my conscience. Where I can do good, I will not do evil. Oh Lord, help me; you have given birth to me in a Rajput family. Don't let my actions shame this great community. No, never. This head will not bow before selfishness. I am a descendant of Ram, Bhishma, and Pratap. I will not become a servant of my body.

At that moment, Kunwar Jagdish Singh felt as if he had climbed a tall minaret. His mind was filled with pride; his eyes shone. But in a moment, this enthusiasm began to wane; his eyes fell downwards. His whole body trembled. He felt like a man sitting on the bank of a river, contemplating jumping into it.

He thought, will my family agree with me? Even if they agree because of me, do I have the right to sacrifice their desires along with mine? Moreover, my mother would never agree, and perhaps my brothers would also refuse. Considering the status of the principality, they are entitled to thousands of rupees annually and I cannot interfere in their share in any way. I am only my own master, but I am not alone. Savitri herself might be ready to jump into the fire with me, but she would never let her beloved son come near this ordeal. Kunwar Sahib could think no more. He rose from his bed in a restless state and began pacing the room. After a while, he looked outside and went out, opening the door. It was dark all around. Like his anxieties, an endless and terrifying river was flowing before him. He slowly walked to the riverbank and strolled there for a long time. An anxious heart loves the waves of water; perhaps because the waves are restless. He focused his scattered thoughts. If all these allowances are paid from the principality's income, it will be difficult to pay even the interest on the debt; let alone the principal! Can’t the income be increased? There are twenty horses in the stable now; one is enough for me. There will be no less than a hundred servants; two are more than enough for me. It is improper to make my own brothers serve below me. I will give them land of my own; they will farm comfortably and give me blessings. The fruits of the gardens are currently being wasted; I will sell them, and the greatest income is from the crops. Ten thousand rupees come from the Maheshganj market. The Mahant takes all this income. He should get a thousand rupees a year. I will now take the lease of this market; I will get no less than eight thousand. From these sources, the annual income will be twenty-five thousand rupees. A thousand rupees is enough for Savitri and Lalla (son). I will tell Savitri clearly that either take a thousand rupees monthly and stay with me, or take half the principality's income and leave me. If she wants to become a queen, let her, but I will not be a king.

Suddenly, Kunwar Sahib heard a voice – "Ram Naam Satya Hai." He turned around. Several people were carrying a corpse. They built a pyre on the riverbank and lit a fire. Two women wailed. This lamentation had no effect on Kunwar Sahib's mind. He was ashamed of his heartlessness! A poor man's body was burning, women were weeping, and my heart does not melt! I am standing like a stone statue. Suddenly, a woman cried, "Oh my king! How sweet did the poison taste to you?" Hearing